Dirección Xeral de Saúde Pública Galicia

Cannabis

Abstract: Abstract

Cannabis is the most widely used illegal psychoactive substance among young individuals. Early onset of use is associated with problems in school performance and early school drop-out, as well as an increased presence of mental disorders (anxiety, depression, psychosis) in adulthood. Earlier use and higher frequency of use indicate greater risks.

Keywords: cannabis; epidemiology; intervention

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, greater attention has been paid to the potential

public health implications of cannabis use. This is due to several

reasons, among them, the widespread use of cannabis among the

Spanish and European population in general, the increased number of

demands for dependency treatment, and the increased number of

conditions associated with cannabis use.

Cannabis is a plant containing over 421 chemical compounds, 61 of

which are cannabinoids, with D9-THC having the highest psychoactive

capacity and contributing the most to the toxicity of cannabis.

The onset of cannabis use typically begins before the age of 15

and is more frequent in males, who have a higher prevalence of use

of other related drugs (alcohol and tobacco).

The onset of cannabis use has to do with many factors, one key

factor being “peer pressure”, compounded by the low risk perceived

by the youngest, which leads to the normalisation of cannabis use in

these age groups.

Easy access to this drug (even if it is an illegal psychoactive

substance) means that there is now a higher incidence of consumption

among the younger population.

DATOS EPIDEMIÓLOGOS

Cannabis remains the most widely used illegal psychoactive

substance in Europe, in all age groups

(Informe Europeo sobre Drogas Tendencias y novedades, 2018)

.

This psychoactive substance is usually smoked and, in Europe, is

often mixed with tobacco. Cannabis use patterns range from

occasional to regular to dependent use. Most cannabis users are

experimental or occasional users. However, in a significant

proportion of cases, the pattern of cannabis use increases the risk

of suffering health effects, poor academic and work performance,

and/or developing a dependency.

About 26.3% of European adults (15-64 years) are estimated to

have used cannabis at some point in their lives. Of these, it is

estimated that 14.1% of young adults (15-34 years old) used cannabis

in the last year, 17.4% of them between 15 and 24 years old. Among

those who consumed this psychoactive substance during the last year,

the ratio of males to females was two to one.

The results of the latest survey show that, in most countries,

cannabis use has either remained stable or increased among young

adults over the previous year.

According to the Survey on the Use of Drugs in Secondary

Education in Spain

(Ministerio de Sanidad Consumo y Bienestar Social, 2016)

, the consumption of cannabis was

slightly more widespread among males: 15.2% of 14-year-olds had used

cannabis at some point (as compared to 12.6% of females), a

proportion that increases progressively with age, to the point that,

one in every two 18-year-old males (56.3%) had already used it at

some point (as compared to 54.7% of females). Cannabis users also

report a higher prevalence of alcohol and tobacco use.

IMPACT ON THE BODY

Cannabis may be used in the following ways: through inhalation

(mixed with tobacco, vaporised, using a pipe or an electronic

cigarette) or orally (in cookies/cakes, etc.).

Its effects on the body are produced by the activation of

specific cannabinoid receptors (the CB1 receptor, which is

abundantly located in the CNS, and the CB2 receptor, which is

expressed primarily on the cells of the immune system). The

activation of these receptors produces the inhibition of the release

of neurotransmitters from axon terminals.

Cannabis use generally produces depressant-type effects, mild

euphoria, and alterations in perception (distortions in time

perception, intensified regular sensory experiences). It may also

produce anxiety, panic, paranoia, psychosis, depression, inhibition

of motor skills, as well as muscle relaxation.

These reactions are dose-dependent.

Immediately after consumption “cannabis intoxication” occurs,

with symptoms like dry mouth, red eyes, tachycardia, lack of

movement coordination, uncontrolled laughter, drowsiness, and

alterations in memory, attention, and concentration.

ADRESSING CANNABIS USE

It is important to make an early detection of cannabis use in

order to intervene as soon as possible on the individual and their

environment by offering personalised care. Paediatric professionals

should inform parents when they detect any “warning signs”.

Suspicion of consumption. Warning signs:

-

Behaviour and mood shifts.

-

Neglect of personal hygiene.

-

Deterioration of family relationships and their environment

in young individuals.

-

Poor academic performance.

-

School absenteeism.

If cannabis use is detected, a brief intervention should be

conducted. If such use becomes problematic, the minor may require an

intensive intervention, in which case referral to a specialised unit

might be considered.

Myths about cannabis

As in the case of tobacco, there are misconceptions that have

become entrenched in society regarding cannabis consumption which

must be clarified by professionals.

Many of the misconceptions or myths about cannabis going around

are related to it being innocuous, posing a low health risk because

it is a “natural product”, or being therapeutically useful.

This confusion generated around cannabis consumption, which is

directed at the most vulnerable population, requires interventions

on the part of health professionals, who must provide the general

population with correct information. Only in this way may these

myths be debunked.

DIAGNOSTIC TOOLS

There are useful tools for detecting patients at risk of cannabis

use from the primary healthcare perspective.

There are several scales for assessing cannabis use. The CAST

scale

(Cuenca-Royo et al., 2012)

is a simple 6-question

questionnaire, developed in France, with the aim of detecting

problematic consumption patterns. Ever since this scale was

developed, it has been widely used both in the general population

and in the adolescent population in several countries, and has

proven to be suitable for this purpose.

The use of this scale in primary care would facilitate the

identification of young individuals who may be at risk of developing

a cannabis use disorder, guide the diagnosis, and help them be

referred to specific treatment programmes.

Table 1. CAST. Cannabis Abuse Screening Test

Table 1. CAST. Cannabis Abuse Screening Test

| CAST. Cannabis Abuse Screening Test |

-

Have you smoked cannabis before midday?

-

Have you smoked cannabis when you were alone?

-

Have you had memory problems when you smoked

cannabis?

-

Have friends or family members told you that you should

reduce or stop your cannabis consumption?

-

Have you tried to reduce or stop your cannabis use

without succeeding?

-

Have you had problems because of your cannabis use

(argument, fight, accident, poor results at school,

etc.)?

|

Results:

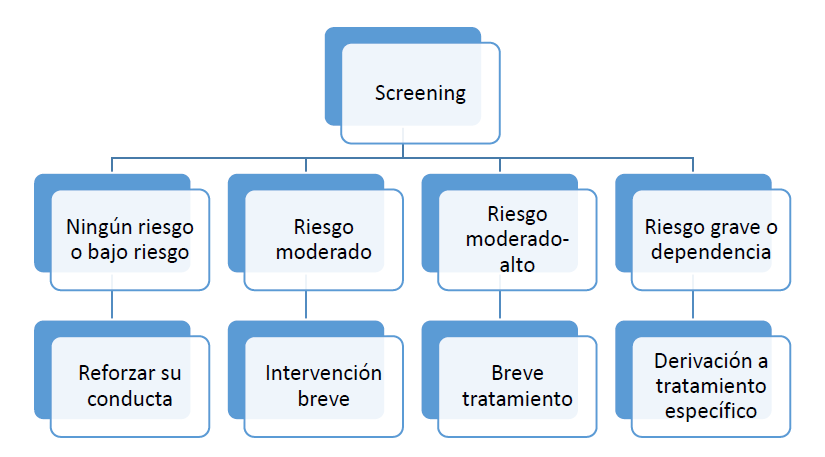

See Figure Figure 1 Esquema de Intervención según el CAST

Figura 1 Esquema de Intervención según el CAST

Fuente: (Legleye, Karila, Beck, & Reynaud, 2007)

Translation Table 2. Spanish – English Figure 1. Intervention plan according

to the CAST scale

Table 2. Spanish – English Figure 1. Intervention plan according

to the CAST scale

|

Spanish

|

English

|

|

Screening

|

Screening |

|

Ningún riesgo o bajo riesgo

|

Little to no risk |

|

Riesgo moderado

|

Moderate risk |

|

Riesgo moderado-alto

|

Moderate-to-high risk |

|

Riesgo grave o dependencia

|

High risk or dependency |

|

Reforzar su conducta

|

Behaviour should be reinforced |

|

Intervención breve

|

Brief intervention |

|

Breve tratamiento

|

Brief treatment |

|

Derivación a tratamiento específico

|

Specific treatment referral |

Interventions in minors will be different depending on the

following:

-

If parents are aware of the minor’s cannabis consumption, the

minor will be asked for permission to include their parents

during the interventions.

-

If parents are not aware of the minor’s cannabis consumption,

the age of the patient and the degree of risk identified after

the screening will be taken into account before including

parents in the interventions.

Different actions should be taken based on the results

-

If no risks are identified, beneficial aspects should be

emphasised and positive and healthy choices should be

reinforced.

-

In the case of non-problematic users, brief pieces of

advice should be provided:

-

I’d recommend you against doing it again. Your brain is

still developing, and using cannabis or other psychoactive

substances may affect its proper development.

-

Cannabis use may interfere with your decision-making and

may cause you to act inappropriately.

-

In the case of problematic consumers, more intensive

interventions are needed. Establish an action plan with the

user, including individualised and personalised

objectives:

-

Agree to a withdrawal for a certain period of time (4-8

weeks), with the goal of making them aware of the

seriousness of their problem.

-

Establish strategies to avoid consumption.

-

Monitoring and reinforcing the milestones achieved.

If these objectives are not achieved, refer to a specialised

unit.

GENERAL RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PAEDIATRIC

PRACTICE

Paediatric professionals should emphasise the following

points:

-

Cannabis is addictive.

-

Cannabis use is closely related to the consumption of other

substances (alcohol and/or tobacco).

-

THC (tetrahydrocannabinol) is the main active ingredient in

cannabis. It is a very fat-soluble substance that reaches the

brain quickly, where it accumulates, and the body eliminates it

eliminated very slowly. It has long-term effects: cannabis

consumption during weekends tend to accumulate, since one week

after consumption, the body has still not managed to eliminate

more than 50% of the substance.

Even if an individual only consumes cannabis at the weekends, it

is not enough time for the body to eliminate it completely and it

will therefore accumulate in the brain, producing different

effects.

-

Cannabis use is associated with poorer or failed academic

performance. The negative effects of cannabis use on attention,

motivation, memory, and learning skills may last for days and

even weeks after the immediate effects have worn off.

-

Like most psychoactive substances, cannabis use may impair

decision-making skills, which may be conducive to engaging in

risky behaviours.

-

Attention should be paid to the occurrence of symptoms of

accidental cannabis poisoning in previously healthy children who

now present with acute neurological symptoms for unknown

reasons. It may be useful to make a differential diagnosis with

other conditions such as hypoglycaemia, CNS infections, etc.

Urine toxicology testing should be requested to confirm acute

exposure to cannabis.

-

Smoking cannabis during lactation is a risk factor for sudden

infant death and has been associated with delayed motor

development at one year of age. The fat-soluble nature of

cannabis causes THC to accumulate in breast milk up to 8 times

more than it does in the mother’s body.

License Creative Commons Attribution -NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International

License Creative Commons Attribution -NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International